| tags:mapper rstats topological data analysis categories:methodology

the mapper construction in base R

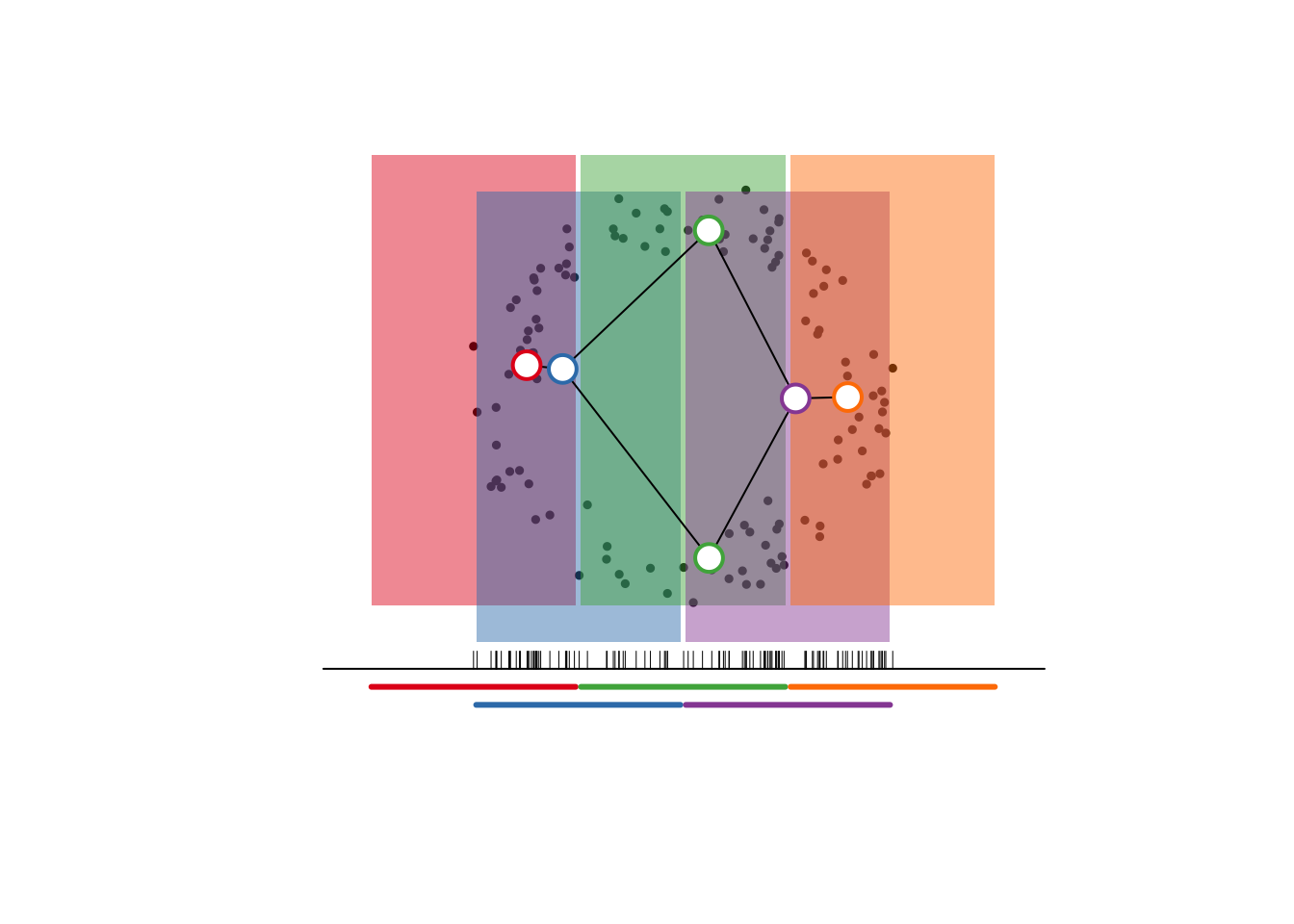

Several mature, open-source implementations of the mapper construction now exist, including the standalone Python Mapper module and KeplerMapper, part of the scikit family. I’m currently experimenting with Matt Piekenbrock’s R package Mapper, which is not on CRAN but makes—from my beginner’s vantage point—exemplary use of the R6 system.1

What these implementations have in common is that the underlying construction is mostly hidden from view. Users can specify its constituent parts, but what gets visualized is almost exclusively either

- the lensed (or filtered) point cloud, usually in two dimensions; or

- the simplicial complex, usually annotated by size and color.

This is fine of course for routine experimental or practical use, but it limits the pedagogical potential of these tools.

The most rapidly i’ve come to understand the construction has been through implementation. In fact, it’s tedius but not terribly time-consuming to construct a mapper entirely in base R.2 The following “implementation” is taken from a document i’ve been using internally to convey the basic idea of mapper and to illustrate the effects of different choices of cover. Maybe you can find more illustrative uses for it, but i recommend against building an analysis pipeline around it!

precap

Briefly, here is some notation for the elements of the construction, adapted from Mémoli and Singhal:

- \(X\) – the point cloud (a finite metric space)

- \(f:X\to Z\) – the lens function from \(X\) to the lens space \(Z\)

- \(\mathcal{U}=\{U_i\}\) – the cover of \(f(X)\), usually inferred from (and used interchangeably with) a finite cover of a subset \(S\subset Z\) that contains \(f(X)\)

- \(\delta:X\times X\to\mathbb{R}_{\geq0}\) – the distance metric on \(X\)

- \(C:\mathcal{M}\to\mathcal{P}\) – the clustering method, based on \(\delta\), that sends metric spaces \(Y\subseteq X\) to partitions of their elements

- \(\mathcal{V}=\{V_{ij}\}=\bigcup_i{C(f^{-1}(U_i))}\) – the refinement of the pullback cover \(\{f^{-1}\mathcal{U}\}\) of \(X\) obtained by partitioning each subset \(f^{-1}(U_i)\subset X\)

- \(N\) – the nerve of \(\mathcal{V}\), comprising a simplex for every non-empty intersection of sets in \(\mathcal{V}\)

construction

I’ll begin with probably the most common toy example, the noisy circle. Since this isn’t part of the construction per se, i’m allowing myself the vanity of invoking a manifold sampling package under development with two high school interns:

set.seed(2)

# point cloud

x <- tdaunif::sample_circle(n = 120, sd = .1)

x[, 2] <- x[, 2] + 1.5

print(head(x))## x y

## [1,] 0.21900250 2.3144202

## [2,] -0.09167245 0.4182471

## [3,] -0.96604574 1.0946227

## [4,] 0.50825992 2.2572006

## [5,] 0.98900895 1.2088241

## [6,] 0.85559229 1.2699230I’ve shifted the coordinates upward for downstream plotting purposes. Note that this point cloud \(X\) exists in \(\mathbb{R}^2\) but that i have not yet declared a distance metric \(\delta\) on \(X\).

The lens (or filter) \(f\) is usually (a) obtained via dimensionality reduction on the \(X\) or (b) taken to be a meaningful stratification variable of or function on \(X\). This example takes approach (a), projecting \(X\) to its first coordinate:

# lensed point cloud

f <- x[, 1]

print(head(f))## [1] 0.21900250 -0.09167245 -0.96604574 0.50825992 0.98900895 0.85559229For ease of visualization as well as personal preference, i’ll use a fixed-width interval cover \(\mathcal{U}=\{U_i\}\) with diameter half that of \(f(X)\) and 50% overlap, which comprises five sets. I like this sort of cover because it is (uniformly) 2-fold—every point of \(f(X)\) is contained in exactly two \(U_i\):

# cover interval length

d <- diff(range(f))*1/2

# cover interval centers

c <- seq(min(f), max(f), d/2)

# cover intervals

u <- cbind(x0 = c - d/2, x1 = c + d/2)

print(u)## x0 x1

## [1,] -1.748626379 -0.586016272

## [2,] -1.167321326 -0.004711219

## [3,] -0.586016272 0.576593835

## [4,] -0.004711219 1.157898888

## [5,] 0.576593835 1.739203942The pullback cover \(f^{-1}(\mathcal{U})\) of \(X\) is a straightforward step that involves no choice on the users part, though note the use of <= and < to ensure (up to mechanical precision) that cover set boundaries are handled correctly:

# pullback cover sets

p <- apply(u, 1, function(u_i) which(u_i[1] <= f & f < u_i[2]))

names(p) <- paste0(seq(p), ":")

print(lapply(p, head))## $`1:`

## [1] 3 9 10 11 15 19

##

## $`2:`

## [1] 2 3 9 10 11 15

##

## $`3:`

## [1] 1 2 4 7 8 12

##

## $`4:`

## [1] 1 4 5 6 7 8

##

## $`5:`

## [1] 5 6 17 20 29 30To partition the preimages \(f^{-1}(U_i)\in f^{-1}(\mathcal{U})\), i’ve used the theoretically exceptional method of single-linkage hierarchical clustering, but with a dangerously naïve fixed cutoff at height \(\frac{1}{3}\):

# clustered pullback cover sets

cl <- function(p_i) {

m <- cutree(hclust(dist(x[p_i, , drop = FALSE]), method = "single"), h = 1/3)

lapply(unique(m), function(v_ij) p_i[which(m == v_ij)])

}

v <- unlist(lapply(p, cl), recursive = FALSE)

print(lapply(v, head))## $`1:`

## [1] 3 9 10 11 15 19

##

## $`2:`

## [1] 2 3 9 10 11 15

##

## $`3:1`

## [1] 1 4 7 12 14 18

##

## $`3:2`

## [1] 2 8 13 16 21 23

##

## $`4:`

## [1] 1 4 5 6 7 8

##

## $`5:`

## [1] 5 6 17 20 29 30While the clusters \(V_{ij}\) will be encoded as vertices, higher-dimensional simplices will represent overlaps \(V_{ij}\cap V_{i'j'}\) among them (\(i\neq i'\)). Happily, because the cover is 2-fold, any lensed point \(f(x)\) lies in the intersection \(U_i\cap U_{i'}\) of at most two cover sets, so in this case we only have to worry about edges between pairs of vertices. Moreover, the only intersections to check are those between cover sets of adjacent indices \(i'\in\{i-1,i+1\}\):

# matrix of pairwise overlaps

b <- matrix(NA, nrow = 0, ncol = 2)

for (ij in seq(length(v) - 1)) {

i <- as.integer(gsub(":.*$", "", names(v)[[ij]]))

i1js <- grep(paste0("^", i + 1, ":"), names(v))

for (i1j in i1js) {

if (length(intersect(v[[ij]], v[[i1j]])) > 0) {

b <- rbind(b, c(ij, i1j))

}

}

}

print(b)## [,1] [,2]

## [1,] 1 2

## [2,] 2 3

## [3,] 2 4

## [4,] 3 5

## [5,] 4 5

## [6,] 5 6(It’s possible, just cumbersome, to handle arbitrary covers and arbitrarily high-dimensional simplices.)

visualization

The whole process is visualized below, also in base R (with the exception of a ColorBrewer palette), with comments separating the steps. To construct constituent frames of a gif or slideshow, just execute progressively more commented chunks from start to end.3

plot.new()

plot.window(c(-1.25, 1.25), c(-.25, 2.75), asp = 1)

# point cloud

points(x, pch = 19, cex = .5)

# lens

lines(x = c(-2, 2), y = c(0, 0), lty = 1)

rug(f, pos = 0)

# cover

u_cols <- RColorBrewer::brewer.pal(nrow(u), "Set1")

segments(

x0 = u[, 1] + .015, x1 = u[, 2] - .015,

y0 = c(-.1, -.2), col = u_cols, lwd = 3

)

l_nudge <- rep_len(c(T, F), length.out = nrow(u))

# pullback cover

rect(

xleft = u[, 1] + .015, xright = u[, 2] - .015,

ybottom = .15 + .2*l_nudge, ytop = 2.65 + .2*l_nudge,

col = paste0(u_cols, "77"), border = NA

)

# nerve

n_lay <- t(sapply(seq_along(v), function(i) {

apply(x[v[[i]], , drop = FALSE], 2, mean)

}))

for (i in seq(nrow(b))) lines(x = n_lay[b[i, ], 1], y = n_lay[b[i, ], 2])

points(x = n_lay[, 1], y = n_lay[, 2],

pch = 21, cex = 2, lwd = 2, bg = "white",

col = u_cols[as.integer(gsub("^([0-9]+)\\:.*$", "\\1", names(v)))])

I’m pretty sure that this is the only visualization of mapper i’ve seen that

- comes from an implementation on a non-trivial point cloud and

- represents every step in the construction.

I general, it would be difficult to visualize the mapper internals like this, for example when \(Z\) isn’t low-enough-dimensional or \(f\) is not a linear projection of \(X\). But i think it poses an interesting challenge—for example, given any lens \(f:X\to\mathbb{R}\), to find a map \(g:X\to\mathbb{R}\) such that \(x\mapsto(f(x),g(x))\) roughly preserves distances—and i’d be keen to see the results.

I’m in a book club with a colleague on Wickham’s Advanced R, and we should arrive at the R6 chapter in a month or two.↩

OK, i’m actually using the usual distribution of R, including

stats::hclust()for example.↩I’ve used the resulting images in a slideshow to mixed effect. Be sure to check slides on the system you’ll be using to present them!↩